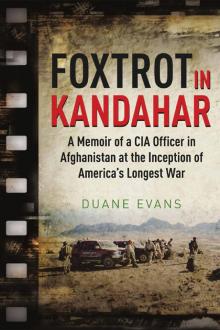

Foxtrot in Kandahar Read online

Page 3

My long-term career intention was to work in federal law enforcement, and I majored in Police Science toward that end. No doubt because of my father’s example, however, I believed I had an obligation to serve my country in the military. I obtained a regular Army commission through the ROTC program at New Mexico State University, and subsequently served six years of active duty.

My troop unit service was with what at the time were called Rapid Deployment units, in my case, the 82nd Airborne Division and the 7th Special Forces Group, which I had wanted to join since reading The Green Berets by Robin Moore when I was a kid. I believed that if there was a conflict it was likely I would be deployed. As it happened, with the exception of the Granada action and the invasion of Panama, neither in which I participated, my Army years were during peacetime and I spent my time training for a contingency that never arose. I left the Army thinking I had gotten off lightly, particularly in comparison to my father who had spent years of his life at war, and then spent the rest of his life having nightmares about it.

Once I decided to leave the Army, it was my father who pointed out a CIA recruitment advertisement in the Army Times and suggested I might want to apply. I had not really considered the Agency for a career, believing that I would probably need to speak a foreign language and have a Master’s degree, neither of which turned out to be a requirement. I applied, and to my amazement, was hired and became an operations officer, also known as a “case officer” in the CIA’s Directorate of Operations, or D.O.

On 10 September 2001, I was 45 years old and married with two kids. I had completed multiple, traditional CIA tours overseas and at Headquarters, and I had been out of the Army for almost 18 years. The last thing I would have imagined was that I might soon be headed into a war zone.

4

A Day Late

In THE FIRST DAYS following the 9/11 attacks, I spent my time at Headquarters trying to join whatever office would head up CIA’s response. That proved to be harder than I’d thought it would be.

In the immediate aftermath of the attacks, it was unclear which office would be given the lead responsibility for CIA’s role: NE Division or the Counterterrorist Center, known as CTC. NE’s area of responsibility included the Taliban-ruled country of Afghanistan that served as al-Qa’ida’s sanctuary. This meant that NE owned the turf, in terms of the U.S. intelligence interests and operations there. CTC, on the other hand, had no territorial responsibilities, but was charged with the worldwide counterterrorist mission. Not knowing which office would take the lead, I hedged my bets by staying on leave status for several days, even as I walked the sterile corridors of Headquarters trying to learn as much as I could about what was happening.

Soon I heard that CTC would be in charge and had already organized a team that would be deploying to Afghanistan. The CTC team’s mission was to link up with the Northern Alliance, an Afghan organization made up of Tajik, Uzbek, Turkmen, and Hazara minorities that had been fighting the Pashtun Taliban for years. Importantly, the Northern Alliance was the only organized anti-Taliban force that held territory in Afghanistan. The CIA team, whose formal designation was the Northern Alliance Liaison Team (NALT), code-named “JAWBREAKER,” would be led by Gary Schroen, a highly experienced and decorated operations officer. Gary was in the agency’s retirement transition program on 9/11, but given his relevant and much needed experience, he was asked to delay his retirement in order to lead the NALT. Gary readily accepted the dangerous assignment.

CIA was not a stranger to the Northern Alliance, having maintained contact with the organization for years. During that time, CIA teams had made trips inside Afghanistan to keep up the liaison contact. Complicating Gary’s task, however, was the recent assassination of Ahmad Shah Masood, the Northern Alliance’s charismatic and legendary military leader, who was killed only days before the 9/11 attacks by a suicide al-Qa’ida team posing as journalists. With Masood gone, it was not clear how the Northern Alliance would be impacted in its ability to continue the fight against the Taliban.

The NALT’s mission was especially critical as it was the first step of the U.S. strategy developed by CTC under the leadership of Cofer Black. Importantly, in keeping with the Bush Administration’s preference, the strategy avoided the use of conventional U.S. ground forces. Instead, it called for small, combined teams of CIA and U.S. Special Forces personnel to deploy to Afghanistan to work directly with the Northern Alliance forces, as well as other armed Afghan groups. Their mission would be to locate and destroy al-Qa’ida, and as necessary, Taliban forces. A major component of the plan would be U.S. air power that would be used to attack strategic enemy targets and provide close air support to the friendly Afghan fighters acting as the surrogate maneuver forces on the ground.

After I heard about the formation of the NALT, I talked to NE Division management and obtained their agreement that I could stay on with CTC for the next several months. I immediately set out to find Gary Schroen to let him know I was available and would like to join his team. It took me a couple of days to run him down, as he proved to be a moving target, busy as he was trying to put his team together and make the necessary preparations for deploying.

I knew Gary from earlier in my career but not particularly well, and I had never worked directly with him. I really wasn’t sure he would even remember me. I decided that, if presented with the opportunity, I had to make a good case for why he should take me with him. Finally, purely by chance, I ran into him at the NE Division front office.

“Hi, Gary. I understand you’re putting together a team to deploy to Afghanistan.”

“Yeah, Duane, how are you doing?

Well, at least he remembers me, I thought.

“I’m finalizing the arrangements right now,” he continued.

“If it’s not too late, I’d like to join your team. I just came back from a COS position with CTC, and I’m available to deploy. I’m a former Army Special Forces officer and I speak Farsi.”

I figured my military background, although admittedly dated, would be valuable given the team’s destination and mission, so I made sure Gary knew about it. I also threw in the part about speaking Farsi as he himself was a Farsi speaker, and the Persian Farsi was similar to the Dari spoken in parts of Afghanistan.

Gary looked at me for a second.

“Well, it’s not clear when we’re going to leave, but it could be any day. I’ve got a meeting right now, but let me check into it. I’ll get back to you tomorrow.”

Although my encounter with Gary was brief, my goal was accomplished, and the next day I met with him again. The news was positive.

“You better start getting some gear together ASAP. Things are moving quickly and there’s a good chance we’ll leave very soon.”

It looked like I was going to get what I had asked for, but with possibly just a day or two to prepare there was very little time to get myself organized. The family and I were still living out of suitcases in a temporary apartment, and I had no gear or clothing with me that would be suitable for the environment and the mission. Gary had said I should go out and buy what I needed, as the Agency had no clothing or gear to issue me at Headquarters.

The only good thing about the timing of all this was that my wife, who had been stranded in Europe for several days trying to get a flight home, was finally back and she could take the lead in running the household so I could focus on getting ready for imminent deployment.

But my worrying about how I would get everything together in such a short time was wasted energy. It turned out the team’s departure had suddenly been moved up and on 19 September, the same day that Gary and I had last talked, the team left—without me.

Too late in my effort to join Gary’s team, my only alternative was to join the office that would oversee the Afghanistan effort and then try to get on another team. After a couple of false leads as to the office’s location, I finally was directed to a suite in the New Headquarters Building. At first I thought the place was deserted, but then I

found a little corner office with three people sitting in it. I introduced myself to a clear-eyed man of bearish stature who, because he sat behind the only desk, seemed to be in charge. His name was Frank, and he told me I had come to the right place.

With a sweep of his hand he said, “This is CTC/Special Operations, and we’re going take the war to al-Qa’ida.”

I glanced over at the only other people around, a man and woman who did not appear to be doing much of anything at the moment, and said, “Well, it sure looks like you could use a little more help.”

Frank laughed, “Oh yeah, we’re just getting started. Hank Crumpton has just been selected to be our chief, and he’s still en route from overseas. Other than Joanne and John here, and a few stray dogs and cats, this is all the staff we have for the moment.”

“How do I sign on?”

“Well, we’re looking for qualified volunteers, but this is going to be a different kind of mission than the D.O. typically takes on. Hank has said we’ll vet everyone before official acceptance. I’ll have to review your file and confer with him when he gets to Washington. Then, I’ll let you know.”

I knew Hank already. He had been one of my Headquarters overseers while I was a COS in Latin America. I was glad to hear he would be in charge. When it came to CT operations, he was deadly serious. In fact he had been pushing for a much more aggressive policy against al-Qa’ida long before 9/11. I figured this was why he had been chosen to head up the CIA’s response to the attacks.

“Sounds like a plan,” I said. “I’m not sure who is holding my personnel file right now, CTC or NE.”

“Don’t worry. We can track it down.”

Frank jotted down his secure number on a post-it and handed it to me. “Check back with me in a couple of days.”

In two days I called him. He apologized, saying he had been unable to lay his hands on my file. Apparently neither CTC nor NE could find it.

“I’ll see if I can run it down,” I told him.

My efforts were also futile. My file was nowhere to be found, and I was starting to get more than a little frustrated. I knew time was of the essence. I had already missed being part of Gary’s team, and now, because my file had apparently fallen in a large crack between CTC and NE, I was wasting my time walking the halls of Headquarters. This should not be this hard, I thought to myself.

A day or two later, I ran into Frank. “Hey, I was just about to call you. Forget about looking for your file,” he said. “Hank is here, and I ran your name past him. You’re in. Welcome to CTC/SO.”

5

A Threshold Crossed, A Spark Ignited

The ATTACKS ON SEPTEMBER 11, 2001 were not the first time a terrorist act had captured my undivided attention. That distinction, that first entering into my consciousness of terrorism as a phenomenon, occurred in the late summer of 1972 when I was between my sophomore and junior years of high school. My father had just been transferred from New Mexico to Washington, D.C., and we were temporarily living in the Breezeway Motel in Fairfax while we looked for a house.

This was not a happy time in my life. I had just left a state I loved and all the friends I had ever known. I was dreading the idea of starting a new school where I didn’t know a soul. The only thing that gave me any solace was the hope that if I could only make it through the next two years—which seemed like an eternity then—when I graduated, I would return to New Mexico and attend college.

My feelings of loneliness and gloom were only made worse when our much loved black and tan miniature dachshund, “Smoochy,” succumbed from wounds received after being mauled by a pack of large dogs. The fact that Smoochy, whose courage far exceeded his physical abilities, had caused the incident by charging into the dogs, believing he was defending his owners, provided little comfort.

During those melancholy days the Summer Olympics were taking place in Munich, Germany, and I spent many an hour in our small hotel room watching the various competitions, grateful for the diversion. When the first news reports began to break that something was amiss at the Olympic Village, I was immediately drawn into the developing story. Soon the world learned that Israeli athletes had been attacked and were being held hostage. The armed hostage-takers were radical Palestinians from a group known as “Black September.” They were making pronouncements and demands that, if not met, would result in the death of the hostages.

I was shocked by what was happening. Who were these people, these “Black September” radicals? Did they seriously think they were going to accomplish their goals? And did they really believe they were going to get away with it? It seemed crazy. At times, one of the hostage-takers would even brazenly step out in the open on an apartment balcony, his head covered by a ski mask, seemingly unconcerned about being shot. Was he nuts?

The audacity of the attack was mind-blowing to me. It contravened what I knew or had assumed about how people were supposed to behave. This was the Olympics after all. Countries and the people of the world were supposed to come together in peace, putting aside their differences in pursuit of athletic competition. What was going on?

As the events unfolded I remained glued to the drama, following it to the bitter and tragic end. I did not go to bed, as the rest of my family did, when the late night TV news reported that the hostages were safely rescued by police and the radicals were dead. For some reason I doubted that this rosy outcome was true, and I stayed up waiting for more details. Later, when an accurate report did come, the news was terrible. Not only were the hostages not safe, they were all dead—eleven in total. Five of the eight Palestinians were killed and three captured.* As the news sank in, I sensed that a threshold had been crossed, that the rules of civilization that previously existed no longer did. The doors of the world had been opened to whatever evil desired to walk through, and I was gripped by a sense of foreboding. I’m certain this feeling was magnified by the general malaise I was already experiencing. Even so, after all these years, that same feeling surfaces each time a major terrorist incident occurs.

The 1972 attack at the Olympics was a catalyst for me. It sparked a serious interest in international affairs and national security issues, including terrorism, which I continued to follow as I progressed through high school and college. My commissioning into the Military Intelligence branch of the Army after college enabled me to follow these interests in a professional realm. By the time I had entered the Army in the late ‘70s, counterterrorism was evolving into a more formalized field. Within the Army the premiere counterterrorism element, popularly known as “Delta Force,” had formed and was actively recruiting from the ranks.

At the time I was serving as a platoon leader in the 82nd Airborne Division at Ft. Bragg, North Carolina, and I was envious when one of my battalion’s company commanders successfully made it through the selection program for Delta. I was interested in joining the force myself because special operations and the counterterrorist mission had great appeal to me. I was already Ranger-qualified having attended Ranger school as an ROTC cadet, so I thought that might count for something. But after checking with the unit’s recruiters, my hopes were crushed. I was told because I was only a lieutenant and had not completed my advanced branch course, nor served as a company commander, I was ineligible to apply.

I was eligible, however, for Special Forces, commonly known as the “Green Berets.” At that time, Special Forces was not its own branch within the Army and assignment was on a “branch immaterial” basis, meaning it didn’t matter if you were an infantryman or a mechanic, as long as you could pass the SF qualification course you were in. So in late summer of 1980 I transferred from the 82nd Airborne to 7th Special Forces Group located in the Smoke Bomb Hill area of Ft. Bragg. In September I began the SF Officer’s Qualification Course and graduated in December. Although not the Army’s dedicated counterterrorist element, as a direct action-capable force, CT operations were still part of the SF mission, and some of the unit training and specialized courses were directly relevant to that mission. Given t

his, my Special Forces tour helped to advance my understanding of counterterrorism at a tactical level.

In 1982, I received orders for an assignment as an instructor to the Army’s Intelligence Center and School at Fort Huachuca, Arizona. This historic cavalry post, located in the southeastern corner of the state, is where the great Apache chief, Cochise, had once roamed. Although glad to be returning to the Southwest, I left Special Forces with misgivings, but had little choice at the time. I knew my officer status meant I would likely only have one more SF assignment in my career, and only then if I was lucky. In future years Special Forces would become a branch unto itself, allowing officers to spend much of their careers in SF-related assignments, but that change occurred after I had left the Army.

In addition to being in the Southwest, another positive point of my new assignment was that one of the courses I would teach was intelligence support in low-intensity conflict, a topic that included terrorism. This teaching responsibility allowed me to deepen my knowledge and understanding of terrorism through research and working with others knowledgeable in the field.

It was during this assignment that I made the decision to leave the Army. I had already been in for over five years, which was longer than I had intended. I still aspired to a career in federal law enforcement, and I applied to the FBI and DEA. At my father’s suggestion I also applied to the CIA. Although not a law enforcement agency, Dad thought it might be a good fit for me, and the more I thought about it, the more it seemed like it might be an interesting place to work. The CIA was the first to process my application, and in less than a year I was accepted for employment.

I knew the experience I gained from the Army would benefit me in many ways in the coming years at the CIA. What I didn’t know was just how well, seemingly tailor-made, that experience combined with my training and years of operational work at the CIA, would prepare me for when I would join the ranks of CTC/Special Operations.

Foxtrot in Kandahar

Foxtrot in Kandahar